“I always wanted to be a writer. A writer of science, like Carl Sagan. At last, this is the only letter I am getting to write.” – Rohith Vemula

“I always wanted to be a writer. A writer of science, like Carl Sagan. At last, this is the only letter I am getting to write.” – Rohith Vemula

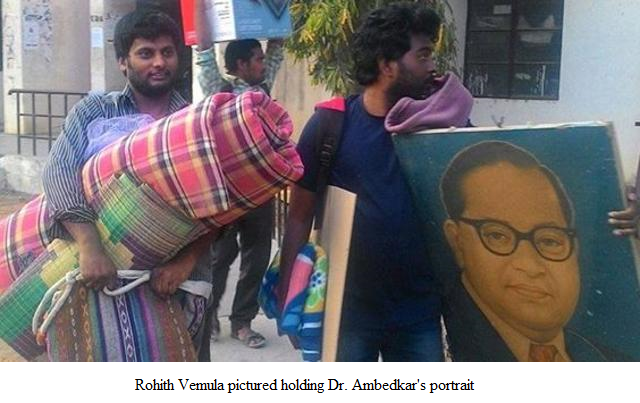

Rohith Vemula, a young Dalit research scholar and student activist of the University of Hyderabad, was interested in life, not death. This is how it is with those who have dreams. Yet, yesterday, on 17 January 2016, he died. Not only did Rohith die, the young man committed suicide.

He killed himself after leaving the protest venue, where he had been living for the past 15 days following his expulsion from the University. He snuck into a University hostel on some pretext and hanged himself there.

But, did Rohit really kill himself? Perusing his suicide note will make it apparent that he did not. He was in fact killed by the phantom limb of caste on which the pretentious democratic credentials of the Republic are superimposed. He was forced into killing himself for standing against and be counted against the continuing crimes of social injustice committed against his people, the ex-untouchables, now treated by the system as dispensables.

Rohith was forced to kill himself because he did not stop at the point of committing a cardinal sin: standing up for his people. He dared to speak for all other marginalized people, be it the minorities, the workers, or women. As a leading activist of the Ambedkar Students Association (ASA), he fought against all injustices and stood by the struggles of the people.

There is nothing new to suicides / cold blooded murder of bright Dalit students in premier educational institutions of India. Many such incidents have been documented in the recent past, in which continuous harassment from the so called upper caste faculties and students have pushed Dalit students to taking extreme steps. A documentary named ‘Death of Merit’ counts 18 such cases in 4 years, up to 2011; the film led to fierce discussions on the subject.

The suicides documented in the film include that of Jaspreet Singh, of the Government Medical College, Chandigarh, who was an extraordinary student. He had never failed, i.e. until he reached the final year of his graduation in medicine. He was failed and was threatened with being failed again and again by the head of his department. Unable to cope up with this torture, he committed suicide, blaming the head of the department for his death. The police refused to lodge a First Information Report against the Professor. The trauma of losing Jaspreet followed by this grave injustice was severe for Jaspreet’s sister, a Bachelor’ student studying Computer Application; she, too, committed suicide,

The outrage over the suicides led to the intervention of the National Commission of Scheduled Castes (NCSC)which set-up a three-member team of senior professors to re-evaluateJaspreet’s answer sheet; the team found that he had, in fact, passed the examination. NCSC’s intervention made the police file the FIR under SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

However, not all the Dalit students killed by the system have been fortunate enough to get even this semblance of posthumous justice.

Even within the pattern of caste-based discrimination leading to such “suicides”, there is something markedly different in Rohith’s case. He, unlike most other young Dalits murdered for their caste by enforced suicide, was not killed behind the walls of educational institutions, away from the public gaze.

One thing common to the other cases is that the world got to know about them after the “suicides”. It is well after the years upon years of mental torture and trauma without support, after the system pushed them out to sea, that the facts became public.

Rohith’s suicide-murder stands apart. It has unfolded under full public gaze, on television, in social media, a gaze that apparently failed to save him.

Further, many Dalit students murdered by enforced suicide were fighting it out all alone, with no support system inside the institutions or in society. Not Rohith. He had his friends, colleagues and common students supporting him in droves. He was expelled from the hostel and hundreds of those not expelled came to sleep out in open with him in solidarity. He, with his activist friends, led a procession in his campus and thousands marched on their own across the country. Yet, he was forced to kill himself and that is what makes this suicide-murder different, and a harbinger of times to come.

These are the times in which a Union Minister, Bandaru Datttreya, intervened with the Ministry of Human Resources Development to discipline “casteist, extremist and anti-national’ elements like the Ambedkar Students Association (ASA).

His primary reason for accusing ASA to be all this was simple: the ASA “has held protests against the execution” of Yakub Memon, a reason which would turn many of the celebrated lawyers of the country including Anand Grover, Prashant Bhushan, Indira Jaisingh, Yug Choudhary, Nitya Ramakrishnan, Vrinda Grover,and others into anti-nationals, for opposing Yakub Memon’s hanging, and seeking, and getting, an unprecedented 5 a.m. hearing by a Supreme Court bench for the same.

Recapping the incidents that led to Rohith’s suicide-murder may shed some more light on times to come for the Republic’s marginalised. His troubles had started when ASA organised a protest march in August 2015 on campus against the attack on the Montage Film Society in Delhi University. That attack was led by the Akhil Bhartiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) because the Film Society dared to screen a documentary movie, “Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai”, which exposes the roles of Hindutva outfits in the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots in Uttar Pradesh.

The ASA protest did not go down well with the local ABVP unit, whose leader Susheel Kumar passed a comment on Facebook, calling ASA members “goons”, for which he later submitted a written apology. Next morning, Susheel Kumar alleged that about 30 students belonging to the ASA had beaten him up and that he had to be hospitalized.

The University’s Proctorial Board conducted an enquiry into the allegations with a medical examination, which could not find any proof of injuries on Susheel Kumar.

The Board observed the following:

“The board could not get any hard evidence of beating of Mr. Susheel kumar either from Mr Krishna Chaitanya or from the reports submitted by Dr. Anupama. Dr. Anupama’s reports also could not link or suggest that the surgery of the Susheel Kumar is the direct result of the beating.”

Based on these findings, the Board, reportedly, warned both the groups to end the matter there.

In an about face, the final report of the Board, however, inexplicably blamed ASA activists for causing injuries to Susheel Kumar and ordered the suspension of five students, including Rohith. ASA organized a protest following the suspension, and held an open discussion with the then University Vice Chancellor Professor R.P. Sharma over the discrepancies in the findings and the punishment. Realising the injustice done to ASA students, Professor Sharma revoked the suspension, subject to the constitution of a new committee to enquire into the incident afresh.

Things started changing course soon afterwards. The new Vice-Chancellor Professor P. Apparao,who took over from Professor Sharma, constituted no committee for fresh enquiry and kept the suspended students in the dark until the Executive Council decided to suspend the students and expel them from their hostels.

It appears Union Minister Bandaru Datttreya’s “intervention” with Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) seems to have played an important role in the decisions taken by the University in this case.

What could have made a Union Minister intervene with the MHRD in such a “small” case, the likes of which are a dime a dozen in campuses across the country? Was it Rohith’s, and ASA’s, attempt to link the struggles of all the marginalized communities that had irked the powers? Was it Dalits standing up for Muslims, another vulnerable minority, something that can puncture the ideological narrative of those in power today?

If so, this is something that should send a shiver down the spine of any conscientious citizen of the Republic. The blame of past suicide-murders of Dalit students in educational institutions lay, primarily, with rogue casteist elements. These elements can be labelled rogue because practicing casteism was never that easy, despite it being deeply entrenched in the system. Harassment of Dalit students in such cases could often be traced back to individual perpetrators. It never was so brazen, with lawmakers intervening to silence voices seeking social justice, by terming these voices anti-national for raising issues, as a united whole, rather than from scattered locations and identities, i.e. the likes of a Dalit, minority, or tribal vantage.

This is also why Rohith’s suicide cannot be seen as an act of desperation. His lifelong struggles did not leave much possibility for him to get desperate. In any case, his suicide note clears the space for doubt. His final letter is not as much a suicide note, as it is an indictment of a Republic that has been failing its vulnerable citizens for long. It is an indictment of the Republic that now seems to be all set to steal even the pretence of justice.

Rohith Vemula’s says it far better in his suicide note:

“The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing. Never was a man treated as a mind. As a glorious thing made up of star dust. In every field, in studies, in streets, in politics, and in dying and living.”

It is this reduction of human beings into mere categories that he fought against all his life. It is this reductionism that he perhaps tried to challenge with one last act of supreme sacrifice. His body, as a body of a Dalit, had always been a site of struggle between forces wanting to dehumanize and own it and those wanting to put an end to this dehumanization.

He turned it into a site that marks the necessity of all liberation struggles joining hands against increasingly vitiating attacks of the old order with new power.

# # #

About the Author: Mr. Avinash Pandey, alias Samar is Programme Coordinator, Right to Food Programme, AHRC. He can be contacted at avinash.pandey@ahrc.asia