The celebration of the 60th Anniversary of the UDHR is a grim reminder that even after 60 years of the adoption of this great declaration the gap between what is declared and what is actually achieved by way of the improvement of the protection of the rights of the people is enormous. Both in the field of civil and political rights as well as economic, social and cultural rights people in Asia, and in fact, the people who live outside developed democracies have so little to celebrate. Instead of wasting this celebration in a self congratulatory fashion it is far more sober to critically examine the real situation faced by the people and to improve the understanding and the resolve to solve the problems depriving people of the rights that have been declared as theirs.

If there is to be a meaningful discourse on the future of the work towards realising the rights declared in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights sharp distinctions must be made about the problems faced in countries outside developed democracies and the way to resolve these. There are grave impediments to the realisation of the UDHR in these countries and they need to be articulated, agreed upon and global efforts must be made to resolve these.

The major impediment to the realisation of the rights declared in the UDHR in Asia is the serious defects in the systems of the administration of justice in the countries of the region. These serious defects of the administration of justice may be related to political and other reasons. However, without dealing with these defective systems the protection of human rights in the region will remain pie in the sky.

As a prelude to a discussion on dealing with this problem the Asian Human Rights Commission thinks it necessary to state this problem more clearly by setting out the distinction between the administration of justice system in countries where the rule of law exists as against those found in most Asian countries.

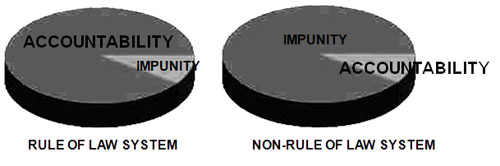

A comparison between the administration of justice system in a rule of law country and those found in non-rule of law countries

This diagram shows that in a developed rule of law system there can still be many defects. For example contemporary experiences about Guantanamo Bay detention centre, introduction of laws even in almost all countries of Europe and the Unites States on restriction to bail conditions for alleged terrorist suspects, many modes of surveillance introduced to foreigners as well as local people in such laws as the Patriot Act of the US and similar laws in other instances and even some disturbing incidents in the failure of the courts themselves to strongly defend the individual freedoms all are indicators of such defects.

However, to compare the situation of the administration of justice systems in many Asian countries (and perhaps all countries in the world outside developed democracies) with the model of the developed country legal system would be misleading and would prevent a proper analysis of the types of problems faced in these jurisdictions.

The diagram demonstrates that within a rule of law system, while there can be many serious defects, these defects can be dealt with within the framework of a well established system of policing, prosecutions and judiciary supported also by a very viable form of expression of public opinion and protest.

As compared to this, what exists in the other model, the non-rule of law model, is an overwhelming situation of lawlessness with some institutions which may be able to maintain a semblance of rule of law, though in fact, the entire system is defective. In these countries there is still legislation enacted in the past, some traditions which have also risen in the course of a long history of attempts to implement such laws, some professions such as the legal profession, the judiciary and the local policing. All these factors have to operate within a much larger framework where rule of law is not considered important at all. Limited developments in the past towards rule of law is very much modified by political systems that have tended to considered these as obstacles to the executive to achieve whatever they want in the manner the?executive thinks fit. Various developments of power models either by way of military interventions or by way of strengthening the hands of the executive and particularly the chief of the executive has conflicted with the limited developments of the rule of law.

The implication of these two models is that the problems faced by ways of limitations on individual freedoms cannot be compared in any meaningful way within the two systems described above. Let us take the case of Guantanamo Bay. Guantanamo Bay detention center was developed in order to deprive the prisoners taken by agencies of the US the rights that are available within the US system of the administration of justice. This means that a very strong and comprehensive justice system does exist in the US but by deliberate attempts some people are being denied the rights that are available within that system. The people who want to fight against such denial have many alternatives. The foremost of them is to call for the abolition of the Guantanamo Bay detention centre and of bringing all persons arrested and detained by US agencies under the law of the US.?In order to achieve this change the reformers can resort to various forms of avenues available for freedom of expression, and also have recourse to the US courts themselves to deal with this problem. The most powerful element available for reforms is the electoral system itself, where abolition of such detention centres outside the law can be agitated for. We have seen that in the recent US elections both presidential candidates promised to abolish the Guantanamo Bay detention centre. The president elect, Barack Obama, has indicated that this issue will be a priority to be dealt with on an urgent basis.

Now, let us compare the avenues available for any person working within a non-rule of law system to deal with a similar problem. Many places, instead of keeping arrested persons even in an illegal prison, the method resorted to is to cause forced disappearances and other forms of extrajudicial killings. The existing legal system has not been proved competent in order to avoid such type of arbitrary executions. There are hardly any possibilities within the local system of administration to get the assistance of courts in order to deal with this problem. Even remedies such as habeas corpus and other modes of urgent applications to courts where these exist are defeated by many problems that exist within the judicial process such as delays in adjudication, big spaces available for witness intimidation and also enormous possibilities of erasing evidence. To put it briefly, the system of administration does not have avenues within which the problem of illegal arrest and detention can be resolved when such acts are done for politically sensitive reasons. Furthermore, the space available for the making of public opinion is also limited. The newspapers and electronic media are themselves subjected to severe restrictions, limitations of the legal system, combined with limitations of avenues of public expression allows the state to also develop enormous propaganda justifying the actions and even to name all dissenters as traitors. As for the electoral process, to make a change of government, again, the avenues available are limited. In most countries now, the electoral process is so manipulated that those who pursue authoritarian policies can ensure for themselves the electoral victories. When all these factors get combined, the result is the loss of confidence in the administration of justice.

There is complete consensus that this is the type of situation prevalent in non-rule of law countries and therefore, any meaningful discourse to resolve these problems should be grounded on a solid understanding of the ground situation within which people live. The attempts merely to compare a superior model and to restate that such a model should be adapted are certainly a laudable aim, but in real terms, it is only a pious hope. To take that approach is to be intellectually evasive and morally timid in that everyone who has some knowledge of these situations of justice administration know that mere restatement of ideas of which a developed system is rooted does not have the capacity to alter the existing situation. In fact, to think and act in that way is to behave like the patients with the phantom limb syndrome. Many amputees of some part of their bodies keep on believing that these parts still exist. To live in a non-rule of law system and to work as if it is a rule of law system amounts to the same form of delusion.

We need to state our problem accurately if we want to find solutions to the problem. Much of our time is spent trying to accurately articulate the existing situation regarding the police, prosecution, judiciary and also the political system and the systems of the public expression within Asian countries. Shocking details about a policing system that cannot in any way be compared to a system that is needed to maintain rule of law, prosecution systems which are so deeply politicized in favor of the existing regimes, judicial systems which are so much subject to corruption as well as to executive control, political systems where the capacity for strong opposition is dealt with by extreme forms of violence and the public opinion making opportunities where terrorizing of journalists and media institutions is the normal experience, is the background of most Asian countries.

Thus the starting point of any discussion on justice administration reforms for the purpose of protecting human rights must begin with understanding, and dealing with this problem.

The requirement for the primacy of place needs to be given to institutional reform for the protection of human rights

Given the defects in the administration of justice mechanisms in the countries of the region the primacy of place in human rights work for the protection and promotion of human rights should be given to institutional reforms, meaning reforms in the policing system, prosecution system and also in the judiciary.

It has been recognised that in that past the human rights related work has concentrated more on human rights education and the search for redress for individuals rather than institutional reforms. Such education redress for individuals may make sense in the context of countries which have developed viable rule of law systems as mentioned above. However, it does not have that impact in countries where the institutional flaws defeat the possibilities for individual redress and does not provide opportunities for education and training to be put to use.

In the state initiatives on human rights often, the donors have been requested to provide technical assistance, meaning various forms of training, particularly for the police but also sometimes, for the prosecution and judicial branches. Sometimes donors have invested their resources in this area. However, when the institutional defects are such as to make the learning and the training of some individuals irrelevant to the normal functioning (or dysfunction) of the institution, such investments in training do not produce the expected results. Let us take the example of the police who may be given training in forensic science and human rights. If the system is so defective that it has not developed the operations on the basis of equality before law, many offenders of the law will have effective impunity and their crimes will not be investigated at all. Thus, there being able persons to investigate such crimes is of no use when as a matter of institutional practice such crimes are not investigated and such offenders are in some way treated above the law. No amount of forensic training can alter that institutional practice. The change of that practice depends on the development of policies and procedures that do not leave any persons or any types of crimes outside the normal operation of the law. This same can be said about the human rights training of the state officers. However much human rights education may be imparted the practical use that such learning could be put into effect depends on the nature of the system itself. If the system is so politicised that it does not want to involve itself on the prevention of violations of rights of certain categories of persons, such learning on human rights will be of little practical value. Actual experiences from many countries demonstrate the wastage of financial and other resources invested in such reforms which are not capable of producing the desired result.

This same can be said of the national institutions which in the region are known as national human rights commissions. When there are fundamental flaws in the systems of policing, prosecutions and the judiciary there is very little that these human rights commissions can do to protect human rights. National institutions cannot take the place of the police, prosecution and judicial branches. The concept of the ombudsman that was developed in Europe after the basic system of the administration of justice were well developed, cannot be applied to institutions in countries where the basic institutions of the administration of justice are fundamentally flawed. In recent decades the donors have invested considerable amounts of resources in national institutions. However, the efforts were doomed to failure due to the lack of appreciation of the fundamental institutional defects which need to be addressed before a proper ombudsman system could effectively achieve the aims for which these are instituted. Here again we come to the problem of the phantom limb syndrome. So-called national human rights commissions in a non-rule of law country can be nothing but a phantom institution.

When considering all these aspects it becomes clear that the human rights work in the region should concentrate on improving the basic institutions of policing, prosecution and the judiciary. The improvements of these systems require an understanding of political, social, cultural and legal aspects that have created the obstacles for the proper operation of the system of the administration of justice. Work towards the improvement of administration of justice systems requires that those who engage in human rights work should above all concentrate on making public opinion to support the changes in the administration of justice. It is only powerful debates within society that can achieve such changes. In creating such debates the human rights groups should expose what is wrong with the existing systems. Such exposures can be done by documentation of what is actually being done in the name of policing, prosecutions and the exercise of judicial power. Both the wrongdoings and the omissions of the system need to be thoroughly documented and be made available to the public. The human rights groups should evolve sophisticated communications mechanisms so that the exposures they make of the system could be made known to large audiences in particular countries as well as globally. As it is natural for the government to deny violations of rights the human rights community must be able to expose such denials as contrary to facts. To do that the human rights community needs to have access to actual details of such violations, the institutional causes of such violations as well as suggestions for improvements.

The preeminent position the police have achieved within the system of the administration of justice has eroded the systems and seriously damaged them

A well functioning administration of justice system creates a healthy balance in investigations into crime, prosecution of crimes and the criminal trials where judicial function is exercised. In the legal text of many of the countries of the region such a system has been envisaged. Most of such texts have been introduced during the colonial times or under the influence of colonial powers. In this way some of the developments of the administration of justice achieved within systems of democracy and rule of law have been introduced into these countries. Therefore it can be said that in most instances as far as legal texts are concerned there are legal safeguards against the police gaining a preeminent position within this system and virtually diminishing the effectiveness of the prosecution and judicial branches.

However, in many countries of the region there is a vast gap between the legal text and how it is operated in actual practice. Over long periods of neglect the police have acquired a preeminent position within the system to the detriment of the other branches of the administration of justice.

In fact, the extent to which the police dominate the administration of justice system in many places is scandalous and leaves very little room for the possibility of proper implementation of law or the achieving of the ends of justice. The abuse of police power provides enormous opportunities for the police to be corrupt and for unscrupulous political and powerful elements of their societies to exploit the police system to their benefit. Often the criminal elements in society themselves build close links with the policing system and thus create a serious threat to the security of the people.

The police investigating capacity can be subverted in the following ways: by undermining the complaint receiving mechanism and by subverting criminal investigations. The receipt of complaints is the beginning of any inquiry into crimes. Unless the complaints are received promptly and efficiently by a user friendly mechanism much of the information and evidence needed to prove a crime can be lost. The police can subvert the receipt of complaints by creating various hardships for making complaints. These may vary from the direct use of the complaint receiving system for extortion purposes to various types of omissions for the protection of alleged offenders, particularly if the offenders happen to be state officers themselves. The narration of various methodologies used for make complaint making difficult or impossible is very common in discussions on human rights in the region.

Perhaps beyond the methods of direct omissions and commissions which obstruct proper complaint making there is the indirect method which is sometimes more effective in creating and maintaining a climate of fear. Once the people begin to realise that through making complaints they may face greater reprisals or that making complaints does not lead to any positive results many people often refuse to make complaints. They themselves prefer or are advised that it is better to remain silent and bear the loss than to complain and suffer greater problems.

In the investigation area the police can obstruct the possibility of achieving justice either by incompetent investigations or by deliberate actions to subvert the investigation. Often large numbers of policemen are used for purposes other than investigations such as providing security to VIPs and often these same persons are given responsibilities for conducting investigations. The development of competence within the system is disrupted often due to political reasons. Good investigators often face punishment transfers or other forms of reprisals. Some even face death. Thus the absence of competence within a policing system is often not a result of the absence of capable and trained personnel, it is often a result of deliberate internal policies which counteract in such a manner to denigrate the appreciation of competence and often plays other aspects such as political loyalties and the capacity for compromise at a higher scale in the system of principles and values within the system.

There is however, another area where investigations are deliberated prevented for political reasons or for reasons of corruption and by the intervention of the hierarchy within the police, acting in cooperation with powerful politicians or other powerful sectors of society. Wherever the state itself encourages the police and military to engage in large scale abuse of rights by actions such as causing forced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, torture and other related activities, the state will also create enormous obstacles for investigations into these matters. In these circumstances the state directly or indirectly approves impunity. This often happens when emergency regulations and anti terrorism laws are allowed to be used. In many countries of the region such laws have been allowed to be used for long periods and often the population has begun to treat this as a normal situation. However, the prevention of investigations can also take place under the influence of corruption where powerful interests mitigate against the proper administration of justice.

A direct cause for the subversion of complaint making and investigation functions of the police is the loss of command responsibility within the policing system as required for its proper functioning. The police hierarchy often makes themselves subordinate to politicians and thereby become an obstacle for the operation of the rule of law. Such subordination may be a result of exigencies of circumstances which the police hierarchy considers beyond their control, or it may be that the police hierarchy themselves try to acquire greater powers for personal advantage through such changes. When command responsibility is damaged the subordinates also develop their own methods of gaining personal advantage from the system. The result is that various forms of gaining personal advantages take prominent place over public interest that the institution of the police is made to serve.

The single most important factor obstructing the proper administration of justice within the region is the predominant place the police have acquired within the system and without addressing this issue it is not possible to achieve any improvement in the protection of rights of individuals

The lack of the allocation of funds for the administration of justice

When budgetary allocations on the administration of justice are compared to other items of the budget it clearly appears that the administration of justice is very much a neglected item. The funds allocated for proper policing, prosecution and the judiciary is so inadequate that the failures of these institutions are predetermined by such absence of financial support.

Often military budgets far exceed the budgets allocated for the administration of justice. This has a doubly adverse impact on justice. With vast allocation of funds for military purposes the military acquires national importance which in turn diminishes the police and the institutions of the administration of justice. The public image of the military grows taller like the image of Alice in Wonderland and as a consequence all other institutions, such as the institutions of justice, education, health and the like grow smaller. On the other hand the legal climate necessary for the military to gain the upper hand often implies the acceptance of impunity relating to the military operations. This in turn reduces the influence of the administration of justice which functions properly only on the basis that no one, including the military itself, is above the law.

What is even more alarming is the policy that is often pursued to the effect that the independence of the institutions of the administration of justice should be crushed in favour of winning the war on terrorism. A former Sri Lankan junior minister of defence put this position succinctly in parliament by stating that these (meaning counter terrorism) cannot be done through the law.?The whole mentality and philosophy behind anti terrorism in the region is that judicial independence is an obstacle to the defeat of terrorism. The view that Great Britain took during the Second World War that victory could be assured only if the courts were independent and functioning is not a doctrine that is accepted in terms of military actions against terrorism in many countries.

Added to this is also the ideology that for development the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary are not essential components. This helps the executive to postpone the considerations about the improvement of the administration of justice as an issue of lesser importance.

Taking all these factors into consideration the human rights movement should make it a priority to agitate for adequate budgetary allocations for the administration of justice. Local and international advocacy should be directed towards achieving this goal. If this goal cannot be achieved much of the discussions and work on human rights will prove incapable of achieving practical results.

The problems of the prosecution systems

A proper system of prosecution requires the following conditions:

?A credible system of receiving complaints

?A credible system of the investigation of complaints

?A credible system of prosecution

?A credible system of defence for the accused

?A credible system of witness protection, and

?A credible system of judicial independence.

The absence of many of these factors affects the prosecution systems in the countries of the region. Often these systems are not created for the purpose of dealing with the prosecution of state officers who violate human rights. Most of these systems were created purely to deal with criminals who mostly come from lower income groups in these societies.

Equality before law has not yet been realised and as such the powerful sectors of society remain above the law. The prosecution systems do not have the will to deal with these issues relating to higher income groups and powerful persons. Most legal systems do not have adequate mechanisms to deal with bribery and corruption. The more prominent beneficiaries of bribery and corruption are higher officers of the state. Powerful business interests also benefit from this because they can take advantage of avoiding legal procedures such as those regarding tenders, contracts and the like. Thus, the prosecution systems only deal with cases competently when the matters are related only to less powerful groups in society. Recent forms of politicisation where the executive tries to control the prosecution systems also act to deteriorate these systems.

Often the prosecutors failure to take effective action is justified by misinterpretation of some legal doctrines. For example prosecutors often claim to be neutral. By this they mean that if the police do not investigate a crime or violation of a right the prosecutor will wash his hands by stating that since the police investigators have not provided them with the dossier there is nothing they can do about the alleged violation. This allows the prosecutors to remain passive and even abdicate their responsibilities. However, what is worse is that this allows the prosecutors to use their discretion selectively. In some instances they may interact with the investigators to ensure a proper investigation while in some instances they will claim that their neutrality prevents them from looking into the alleged violations.

There need to be studies exposing the type of legal doctrines and other excuses used by the prosecutors to abdicate their responsibilities.

The absence of effective forms of witness protection

In most countries of the region there are no effective modes of witness protection. Perhaps given the enormity of the problem such as the predominant place the police have acquired to the detriment of the justice system it may not even be possible to provide for a credible witness protection system.

The witness protection systems require a policing system which is credible. When the policing system can be used to kill and harass witnesses there is hardly any way to protect witnesses. The interested persons may harm witnesses knowing that the police will not pursue them. Or as it has happened in many instances the police themselves will carry out the crimes.

Thus, the whole issue of witness protection requires far greater attention from the human rights community and working towards the creation of an effective system of witness protection needs to be a part of the human rights agenda of all countries.

Attacks on lawyers

The predominance achieved by the police within the justice system has a direct result of diminishing the place of lawyers.

The lawyers who want to be successful in the field of criminal law need to become collaborators with the police. In many instances lawyers have to act as intermediaries to carry bribes to the police and to others. As a consequence they have to compromise on the rights of their clients. The worst is for those who refuse to play such a role as intermediaries. Such lawyers can be blackmailed and otherwise harmed in a way that the clients may feel that a search for justice has to be sacrificed for achieving compromises which may be the only relief they can find within the system.

This is worse for those lawyers who undertake cases against the authorities. They become direct targets for attack by the police or by others who may feel threatened by legal actions assisted by these lawyers.

The all-pervading bribery and corruption

The following incident demonstrates the overwhelming problem of corruption affecting the administration of justice in the Asian region. A law student attended a lecture regarding the prevention of corruption given by a senior lawyer. The senior lawyer mentions many ways of avoiding corruption. The junior lawyer asked the question at the end of the lecture. Sir? he asked, when I join a chamber to practice law soon as I expect, if I am given some money by my senior lawyers to carry to the judge, what do I do??lt;/p>

Perhaps this question sums up the awareness felt everywhere that corruption is all pervasive within their systems. Often dealing with crime becomes a business that benefits many parties, the police, lawyers and their touts and even sometimes judges.

When issues relating to human rights violations come up this corruption becomes even worse. A policemen accused of torture, for example may develop a relationship with a judge directly or indirectly, providing various benefits, even more than what ordinary clients can provide. Thus, while the case proceeds new relationships develop which will benefiting some individuals and having extremely negative impacts on the entire system.

Under these circumstances the struggle against bribery and corruption should be part of the core agenda of the human rights movement. It is impossible to diminish the predominant position achieved by the police without developing anti corruption agencies which are outside the policing system. The Independent Commission against Corruption of Hong Kong (ICAC) is looked into with enthusiasm in many part of the world as a credible model that needs to be assimilated into local legal systems.

The linkage between the promotion of economic, social and cultural rights and resolving the fundamental problems of the administration of justice

The mode by which the majority of populations, who in the Asian context belong to lower income groups, are kept in a powerless position by the denial of the possibility of seeking justice within a functioning legal system also ensures that they have no capacity to assert their economic, social and cultural rights.

The question of entitlements in terms of economic, social and cultural rights can be meaningful only when the justice systems provide the capacity for those who are deprived of these rights to express their grievances and to find avenues through which they can bring pressure upon the state to improve these rights. To have a non-rule of law system with regard to civil rights also implies that the legal milieu that is needed to protect these rights is also absent.

By maintaining a defective system of the administration of justice semi slavery-like conditions can be maintained. The people who are deprived of their right to work need to find ways to highlight their condition and bring the attention of the authorities to resolve them. People who are deprived of rights to education and health need to have avenues through which they could influence public opinion and obtain the necessary measures recognised by the state to respect, protect and fulfill their rights. If the system of the administration of justice is so defective, various forms of reprisals will be allowed to exist in order to suppress people who demand bread, medicine, schools and basic protections for their young.

Without functioning systems of the administration of justice attempts to improve human rights protection can appear to be nothing but loud noise. Unfortunately in the countries of the region the ordinary folk react to the human rights discourse without much enthusiasm due to their realisation that the systems of oppression that exist which are defective administration of justice systems will not allow them to enjoy these rights.

We therefore urge that the global human rights community seriously considers this issue in this season of celebration of the UDHR and arrive at conclusions which supports a human rights strategy which give a primary place for the institutional development for the achievement of human rights.