1. The AHRC model

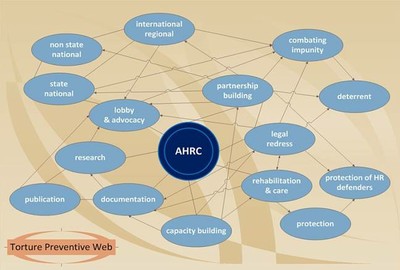

1. The AHRC model (I): An integrated model for linking grass roots with international support

Main Finding: The project utilizes an integrated approach to torture prevention combining service delivery and advocacy at grassroots level with high profile advocacy at regional and international levels. The role of the AHRC is building bridges of solidarity and advocacy between the grass roots through the local partners and the international actors.

This is a unique feature of the AHRC Model.

The model is based on a contextual analysis acknowledging that the local risk level is so high that effective advocacy on torture prevention can not be undertaken solely from Sri Lanka. In other words: “What can be done when nothing can be done”. From this perspective a three-tier action model was chosen with an outside support role for the AHRC to partners within Sri Lanka implementing the project at national level, and where strategies at international, national and local level are expected to coalesce and mutually support each other, thus creating an effective Rapid Response Mechanism.1

Figure 1: AHRC Model (I): Linking grass roots with international support

This expected outcome of integrated strategies was never ‘formally’ defined as an expected outcome of the project. Looking back, we may conclude that the model of an integrated approach to torture combining service delivery and advocacy at grassroots level with high profile advocacy at regional and international levels has certainly been a successful outcome of the project. The model works. The integrated three-tier model is a highly dynamic feature of the project.

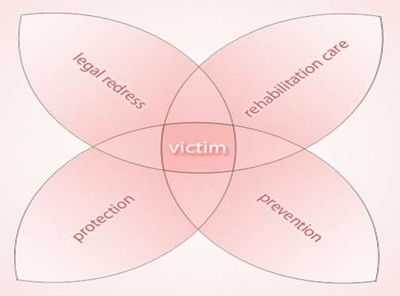

2. The AHRC model (II): Combining advocacy, legal redress, rehabilitation and protection

The AHRC’s model in addressing police torture effectively combines four interrelatedprevention, legal redress, rehabilitation and protection prevention, legal redress, rehabilitation and protection; they form a ‘package’ where the various interventions call for different activities, professional expertise and personal qualities. From the perspective of the victim and his/her family in their process of seeking justice and recovery these areas of intervention are inseparable.

This is an outstanding feature of the project.

For the AHRC this combination has been the outcome of a learning process as the project was initially focused on torture prevention. In the process of assisting the victims for legal redress and appeals, additional interventions were called for such as the need for healing and recovery; and an urgent need for developing protection mechanisms for the victims, their families and human rights defenders2.

Figure 2: AHRC Model (II): Combining advocacy, legal redress, rehabilitation, protection

3. The AHRC model (III): A human rights based approach to torture prevention

The project uses a human rights based approach to torture prevention. The torture victims as rights holders claim their rights to justice. State authorities are challenged to fulfil their obligations as duty bearers. This is to highlight the need for reform of the criminal justice system and the rule of law that are hampered by emergency and anti-terrorism laws.

Police torture is addressed as an opportunity to expose systemic deficiencies in the criminal justice system and the rule of law with torture being practised as standard operating procedure; at the same time highlighting the significance of the fight against impunity.

The AHRC’s rights based approach puts the victims as human being at the centre. Torture violates the very core of human dignity and integrity of a person. In the context of Sri Lanka, it has reached a point where a culture of violence legitimizes routine use of torture in policing work throughout the country.

The impact of torture on individuals, families and communities is put in the context of civil and political rights violations but for the AHRC promotion and protection of economic, social and cultural rights is a matter of priority as well. For the poor it is about the right to food.

4. The AHRC model (IV): Torture as a poverty issue

The AHRC approaches torture as a poverty issue as it found that a root cause of torture is poverty. Based on its extensive database and field practice the AHRC concludes that the majority of torture cases in Sri Lanka do not pertain to middle or higher-class people, but to the poor 3. Poverty is a main risk factor and determinant of torture, and torture prevention strategies should take this into account. The AHRC’s consequent emphasis on poverty as a root cause calls for a theoretical framework that connects torture with poverty, power and Rule of Law4.

The poverty approach informed the project target group and the choice of project partners, and brought the project close to its target group, the rural poor.

2. Assessment of strategic components

As the project evolved, the need for an integrated approach became evident: combining preventive strategies with legal redress and addressing needs of the victims for healing and protection. Care, healing and protection are needed for the victims to muster the courage and perseverance to pursue their legal fight for justice.

This is one of the strengths of the project. The project incorporated the lessons learned.

The combined approach of the four areas (prevention, legal redress, rehabilitation and protection) could be helpful for other organisations in Asia and elsewhere working in the field of torture prevention and rehabilitation; also for RCT. It could be a ‘learning model’ for other organisations. It may be replicable.

1. Preventive strategies

The focus of the project is on prevention. The preventive strategies include Urgent Appeals, lobby, advocacy, campaigns, public awareness, case documentation and reporting, publications, research, media relations, street movement, dialogues5.

The AHRC and its partners excel in routing out torture as a systemic issue at different levels in terms of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights.

The various strategies are interlinked at every level (local, national, regional, international). They constitute a Preventive Web. Victim support feeds into Urgent Appeals and legal redress; Legal redress feeds into advocacy; data collection feeds into research and publications; which are then used for advocacy; partnership feeds into better rehabilitation and care and into better advocacy; public awareness activities feed into victims awareness, trust, increase of caseload; public awareness activities feed into advocacy; international advocacy feeds into national advocacy, protection, organisational profile and funding; capacity building feeds into better rehabilitation and advocacy and partnership building, etcetera6. See below.

Figure 3: Torture Preventive Web

The preventive strategy that has proven to be most effective is the Urgent Appeals7. The Urgent Appeals have undoubtedly served as advocacy tools that contributed to establishing torture as a endemic phenomenon. They serve as a protection tool; they provide awareness and solidarity to the victims with the message that they are not alone in their suffering; they contribute to the victims’ determination to pursue justice.

Outcome: There is evidence that at the results and outcome level there are several achievements that can be attributed to the project’s prevention strategies.

More people are coming forward today to report cases of torture than ever before in spite of considerable risks (killings, death threats, repeated torture, threats to family members) involved in seeking justice. A growing number of people are participating in public action; more publications have come out on torture (urgent appeals, statements, newspaper articles). At least ten books have been published, TV and radio programmes have been realised. Supreme Court senior judges have undertaken a proactive role on the torture issue. The Human Rights Commission adapted a zero policy on torture.

Recommendations

- The evaluators met one victim who did not know that there was an Urgent Appeal about her. It is recommended that victims’ consent be sought. This is primarily an ethical issue. In addition it is a lost opportunity in terms of empowerment. Do the AHRC and partners have operational procedures about Urgent Appeals and publications on issues of consent and privacy? What dilemmas are experienced? Is there a learning process within the organisation in handling these?

2. Legal redress

Legal redress is effective in several ways: for the purpose of highlighting police torture as a systemic issue (prevention) and for rehabilitation of the victim (seeking justice, regaining strength). The AHRC and its partners have faced a huge range of obstacles and dilemmas in fighting for legal redress.8

Victims of torture have the right under the constitution to file Fundamental Rights applications (FR); however the 30-day limit imposed in the constitution for filing up such cases is a major constraint.9 Another constraint that is peculiar for Sri Lanka is the fact that for criminal cases brought before the Magistrate Court it is the local police who assign the lawyers. This affects the independence of the lawyers.10

Legal cases are found to be prolonged battles. Delays of legal cases are considered a reflection of the dysfunctional state of the judicial system preventing and discouraging victims from attaining justice.11

A victim may experience legal redress as a second phase of traumatization, in particular when prolonged delays are involved. Legal redress may hinder the process of recovery; all project partners interviewed in the process of this evaluation acknowledged this dilemma. The evaluators found that the project partners are very apprehensive not to put any pressure on the victims to opt for legal redress; they are aware that it may be in the interest of the victims to opt for a settlement. However it is in the interest of the wider objectives of the project to seek legal redress. It may be recommended that project partners share their experiences in this respect to develop a deeper understanding of this dilemma and an institutional position.

Independent lawyers taking up torture cases are difficult to find in Sri Lanka as representing torture victims puts lawyers at odds with the police, and this against their allies, the magistrates12. The risks for lawyers taking up torture cases are well known and lawyers representing torture survivors have faced serious retaliation from the state and perpetrators13.

A lesson learned by the project is that there is a need for building up a pool of human rights lawyers.

There is evidence that in terms of legal redress, at the outcome level there are several achievements that can be attributed to the project.

In the past cases of torture were not filed as torture cases: only the AHRC started addressing them as torture cases. There are positive Supreme Court decision on five cases of torture of which two were handled by the AHRC; these are landmark cases. Progress is steady but slow. Few cases on police torture have actually been won. Many cases are pending.

A huge and invaluable case documentation has been created and (partly) made available (through the AHRC/ALRC websites); local and international pressure has been built up for almost all cases; a pool of lawyers has been created who are willing to take on and have experienced in handling torture cases; international support has been created for defense of Human Rights defenders; international solidarity has been organised for victim support (in addition to financial support for legal cases14), etcetera.

Recommendations:

- Case conferences / peer discussions between project partners, especially on exceptional cases. Intervision between human rights lawyers.

- Intervision on discrimination experienced by female lawyers.

3. Rehabilitation and service delivery

The AHRC and its partners undertake a wide range of service activities to support victims of torture. The AHRC’s approach to rehabilitation care and service delivery differs from the standard western interpretation of rehabilitation15 in the sense that it sees rehabilitation care as a ‘package of service delivery’ to victims including accompanying victims to the police and to courts, counselling, community based protection, medical rehabilitation, livelihood support, financial assistance et cetera.

RCT has in the past concluded that professional rehabilitation care is the weaker part in the project’s service delivery to victims. “The challenge is to develop treatment models and professionalise without much access to medical doctors or other health professionals.”16RCT recommended assisting the partner network in building a client centred counselling with rules of consultation and assessing the feasibility of different health care models to be integrated in the partner network. In response to these recommendations RCT has facilitated professional support from outside (including through Dr. Mitra17 and Dr. Inger Agger18). The evaluators found that this kind of support and knowledge sharing by RCT is highly appreciated by the partners. There is still a continued need for support in professionalizing health care delivery and professionalisation of counsellors. The evaluators recommend that RCT continue its support to facilitating professionalisation of rehabilitation care, in particular in the following fields: case supervision, counselling techniques, case conferences, victims’ self-help, para-counsellors, self-help groups for livelihood support.

The evaluators witnessed the resiliency and coping capacities of the survivors to heal themselves and help heal fellow survivors. From sharing, they have drawn strength from one another mirroring each other’s experience thereby achieving self-healing in the process. Counselling and testimonial therapy contributed to their individual and collective healing and served as preparation for their cases in courts.

The evaluators observed the need for enhanced rehabilitation interventions for some of the victims in terms of psychosocial professional care. Healing and trauma counselling may indeed not be the strongest side of the project. Faced with the urgent and apparent need to help victims in pain, the local partners, to the best of their knowledge and abilities and with genuine commitment and compassion, have engaged in helping to “heal invisible wounds” 19. They have been pioneers. They did whatever they could, and what they did has to be immensely appreciated. The counsellors and staff of local partner organizations were always ready with their listening ear, a shoulder to cry on, comforting victims and giving them the feeling of not being alone in this fearful battle20. This healing approach is obviously very much valued by the victims; at the same time, however, it is observed that there is space for more shared systematic learning in concepts, methods and tools of healing.

The AHRC in successive project documents has noted that there is a need for more professionalisation in trauma healing in Sri Lanka. In recent years, as part of post-tsunami rehabilitation programmes, there has been an inflow of trauma counselling projects for tsunami victims; this has definitely contributed to a greater trauma counselling human resource base in the country and more people being familiar with counselling. However there has been little coordination and no systematic build up of knowledge.

Self-healing is unique to each and every individual. It depends a lot on the resiliency of individuals and the support system provided by families and communities. It also depends on the life history of the victim and on the extent to which the torture experience comes ‘on top of’ other experiences of abuse, humiliation, poverty, and destitution. This is another reason why an integrated approach to rehabilitation is a prerequisite for effective healing, in particular within a target group consisting in majority of people affected by poverty and discrimination.

The evaluators noted a need for institutionalized staff-care that may include reflection sessions, debriefing and defusing activities, body-work and mindfulness exercises. This need was communicated to the evaluation team on several occasions.

In emergency cases the rehabilitation care provided to victims includes emergency financial assistance21. The allowances are decided on a case basis. It is observed that the issue of financial assistance comes with a lot of dilemmas and constraints: who decides; who may/may not receive, possibility of jealousy, manipulation, personal involvement; what is the impact; the risk of a dependency syndrome. It is recommended that the partners work out guidelines on financial assistance, also from the perspective of “Do no Harm”.

The healing activities have been effective and beneficial, at least for some of the victims met by the evaluation team: “I can eat again”, “I can laugh again”, “When I came to this group I thought I am the only one, but now I know there are many like me”, “I don’t want to forget but I want to fight my case”, “In the beginning I was scared of every uniform but now I can face the police. The police are even scared of me.” These can be seen as indicators for outcome.

There is evidence that in terms of rehabilitation care, at the outcome level there are several achievements that can be attributed to the project to a major extent.

Recommendations

- RCT may continue its support to facilitating professionalisation of rehabilitation care, in particular in the following fields: case supervision, counselling techniques, case conferences, victims’ self-help, para-counsellors, self-help for livelihood support.

- Partners may put greater emphasis on rehabilitation and healing in the follow-up phase.

- A referral network may be developed among partners for rehabilitation care in particular for special cases,

- The network may develop guidelines on how to decide on emergency financial assistance: who, for what, when, how long, how to account for it.

4. Protection

Protection activities include establishment of shelters (church sanctuaries, safe places), emergency actions in case of death threats, transporting victims to another country, logistics, creation of solidarity groups, community vigilance committees, fund-raising.

Protection emerged as a logical and indispensable project component as a direct result of the prevention and rehabilitation work. The project came to venture into protection with the case of Gerald Perera.

Protection involves not only the victim but also his/her entire family, as shown in the cases of Gerald Perera and Sugath Nishanta Fernando. Protection is also required for Human Rights Defenders who experience victimization from state authorities, police and perpetrators (arrests, torture, death threats, attacks and targeted killings). The defense of Human Rights Defenders is an equally indispensable component of a torture prevention programme. In the absence of the State guaranteeing protection of citizens, human rights organisations have no choice but taking up protection.

The evaluators visited three groups involved in organised protection (Home for Victims of Torture, Right to Life and Janasansadaya). At the time of the evaluation mission an urgent need for protection came up with the case of Edward Michael and his wife Mary Allen and daughter Vinoja who need to seek asylum in view of serious death threats posed to them. The issue was raised in follow-up meetings (e.g. with the UN) with no success; this case made obvious that emergency protection needs will continue to surface all along the process of torture prevention and rehabilitation.

HVT and Janasansadaya have been involved in organising victims’ solidarity groups at community level – not only for purpose of rehabilitation but also as a protection mechanism. Some of the victims’ support group have taken the role of village vigilance committees and engaged in a wider range of rights issues. It is premature to speculate on whether such groups may play a further role in addressing grass roots rights and livelihood issues in a broader human rights framework.

Effective protection requires the formation of a broad solidarity front within the country and regionally and internationally. Here, again, the support role of the AHRC comes in.

Unfortunately, the protection offered has not always been sufficient. Combined urgent action calling for protection has not been able to prevent several torture victims (Gerald Perera, Sugath and others) being killed. The office of lawyer Weliamuna has been destroyed. Given the overall repressive framework and deficient Rule of Law, effective fundamental protection is beyond the capabilities of the partners.

It is to be highly appreciated that the shelter homes do not discriminate between torture victims and victims of ‘other’ types of violence. There is a consensus in the humanitarian sector that humanitarian interventions must at any price avoid discrimination between target groups and non-target groups that may lead to tensions about access to resources. Do No Harm.22 It is recommended that RCT, the AHRC and partners develop clear procedures on how to deal with possible dilemmas resulting from the principle of non-discrimination in view of existing funding requirements.

Protection of victims is very costly23. Protection can be a major burden for project funds and human resources, and they are inherently un-planned in that there is no end to them. Protection is a huge operation, also in terms of logistics. Suranji, the wife of Sugath, lived in 17 places in one year with her children. Suranji’s case gives evidence on how protection support is a sine qua non for maintaining the spirit and persistence required for continuing legal redress. Suranji continues to receive death threats but she is adamant that she wants to fight her case.

Recommendations

- Develop policy guidelines on protection procedures,

- Try to establish an (in-country and international) solidarity network on protection including emergency funding,

- Develop procedures on how to deal with possible dilemmas resulting from the principle of non-discrimination in shelter homes, in view of existing funding requirements

1 See also Shyamali Puvimanasinghe: Urgent Appeals and Advocacy: Bridging grass roots and international opinion for change. Praxis paper no 1, RCT, Copenhagen, 2006, p. 25

2 See for example AHRC: Dossier on Gerald Mervin Perera, 2004, and AHRC: The Assassination of Sugath Nishanta Fernando – a Compliant in a Bribery and Torture Case, 2008.

3 “(Janasansadaya, working among) …the poorest in (..) Kaluthara. (…) realised that torture remained one of the major obstacles for the poor in organizing themselves for their betterment.” Project document 2005-2006.

4 C.f. the proposed study on the link between poverty and police torture, Project doc 2005-2006, p 27. See also: B. Fernando and S. Puvimanasinghe: An X ray of the policing system in Sri Lanka and the torture of the poor, AHRC, 2005.

5 See Project Document 2005-2006 and Project Document 2006-2008.

6 E.g.: “The material that is collected (..) in the normal course of trying to provide redress, also becomes the basic direct research material. On the basis of this, further studies can be undertaken, various types of analysis can be done and recommendations to local and international agencies can be developed with a view to redress and reform”. Project Document 2005-2006, p 6.

7 In total over 600 between 2004-2009; in 2009 so far around 40, in 2008 around 90, in 2007 over 100, in 2006 around 150, in 2005 around 135, in 2004 around 100. See AHRC: List of Urgent Appeals from Sri Lanka from 2004-19 October 2009, AHRC, Unpublished document.

8 It has been proposed to lobby for changes of the various constraints (delays, time constraints, police role in assigning lawyers), however it can be argued that lobby for separate constraints may not be opportune in view of a much needed wider lobby for systemic changes in the overall legal framework.

9 According to Prof. O.Espersen this is probably the shortest time limit in the world for filing such cases – see RCT Mission report Nov. 2004.

10 Prof. O.Espersen in RCT Mission report Nov. 2004. Another state tactic making it difficult for a victim to attain justice is case referral to a remote area (e.g., a victim in Kandy whose case was referred to Vavuniya).

11 See: Delays in adjudication, in: Basil Fernando and Shyamali Puvimanasinghe, 2005, p 199-213

12 “…few lawyers, especially outside Colombo, are willing to take up (torture) cases. Representing torture victims puts a lawyers at odds with the police, and this against their allies, the magistrates”: International Crisis Group, 2009, p 20. It is also reported that lawyers taking up HR cases have given questionable advise. One victim was advised to ‘admit’ contacts with LTTE even if he did not have. Other victims have been advised to accept compensation – which they then did not get. Another constraint is that lawyers may charge high fees (up to 150,000 Rs).

13 See also AHRC: Corruption and abuse of Human Rights: Threats and Attacks on a Human Rights Defender. AHRC, 2008; also: B. Fernando, Recovering the Authority of Public Institutions, 2009, p. 245-267

14 for example for the legal case of Ms. Rizana Nafeek (audit report 2007).

15 In fact the Biopsychosocial rehabilitation model (BPS) stipulating a “package of services” is also being applied in the West.

16 RCT: Report, Mission to Sri Lanka June, 2007, by H.Gullestrup, B.Sjolund, J.O.Haagensen, E.Wendt, p. 16

17 HVT documented the training by Dr. Mitra on video.

18 I.Agger: Testimonial Training in Sri Lanka, Report from a Workshop, November 2008, draft; Giving Voice. Using testimony as a brief therapy intervention in Psychosocial community work for survivors of torture and organised violence. Manual for Community workers and Human Rights activists. By C.Perera and S.Puvimanasinghe, and I.Agger. December 2008; I. Agger and S.Puvimanasinghe: Testimonial Therapy and Victims Solidarity Groups, Mission report, October 2009

19 See Richard F.Mollica: Healing Invisible Wounds. Paths to Hope and Recovery in a Violent World. Nashville, Vanderbilt University Press, 2006

20 The evaluators heard many stories about this care both from victims, staff and volunteers.

21 Discussion of the Evaluation team with the Centre for the Rule of Law. Various examples were given, e.g. allowances are given to Lalith (who was breadwinner for his grandparents), Gerald Perera’s family, Rohina, Palitha Tissakumara. Allowances may cover costs of livelihood and medical expenses.

22 see Mary B. Anderson: Do No Harm: How Aid Can Support Peace – or War. Boulder, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1999; Mary B. Anderson (ed.) Options for Aid in Conflict: Lessons from Field Experience, Boulder, 2000. See the Do No Harm framework.

23 as evidenced in cases of Gerald, Lalith and Palitha